If over the last few months I’ve given you the impression that growing White Gum wool is all sweetness and light, November was certainly a counterpoint. It was a tough month, and December followed suit. The refrain has been “desperately dry”—we have had only 60% of our annual average rainfall, and our official 12-month rainfall deficit is sitting in the “severe” category. To add insult to rainfall injury, the ewe wool from this year’s clip tested on the low end for tensile strength, with unhappy consequences for yarn processing, not to mention my self-image.

What happened with the wool clip? Well, it’s about as embarrassing as it gets for someone who spends as much time as I do thinking about sheep nutrition. Wool develops a “tender” area when a sheep has a major change in nutrition, even if it only occurs over the time span of a few days. The position of the break tells you when the problem occurred, and mine happened in mid-summer.

I’ve traced it back to the point when I first started trying to figure out how to do Holistic Management-style rotational grazing, well before I began shepherding. I’m pretty sure that in my enthusiasm for managing the long, rank grass using intensive HM grazing techniques, I wasn’t paying enough attention to the needs of the lactating ewes. They made enough milk to “protect” the wool quality of their lambs, but suffered a break in their own fibre in the process. (The lamb’s wool tested very high for tensile strength.) This is the first time since I began working with nutritional wisdom principles in 2008 that I’ve had a problem with fibre strength, and it was completely self-inflicted.

The experience highlights the subtlety of what’s involved in growing wool well. In particular, I realised I have to ensure the grazing decisions I make err on the side of animal nutrition, rather than landscape management—not always an easy thing to figure out. And if I get it wrong, the consequences now come back directly to me—unlike the old days when I simply auctioned off the fibre and got the best market price I could, given its characteristics. It then became someone else’s problem to deal with!

Now, I’ve got 1200 kg of “tender” ewe wool for Peter Chatterton at Design Spun to figure out how to handle. The low tensile strength means the fibre tends to break during combing. The point of break is the middle of the fibre, creating lots of half-length fibres, with unhappy spinning consequences for worsted yarn. Peter and his spinmeister Matthew have succeeded in spinning a batch of boucle, using predominantly hogget (lamb’s) fibre to protect the weaker ewe wool. Early next year, they will do some experiments to see whether they can spin the standard 8- and 4-ply yarns, which are more demanding than the wrapped boucle, using the ewe fibre. If we're not completely happy with the result, I will probably end up selling the top for "woollen" spinning (e.g. tweed), which normally utilises shorter fibres.

About the only happy note in all of this is I have lots of inventory, so there is no danger of running short of yarn, even if it takes until next year’s clip (which will hopefully be as strong as it should be!) to resupply.

So, not much sweetness and light there.

On the shepherding front, the underlying worry about having enough forage, and whether I would have to sell sheep after all (despite my recent resolution to keep all of my sheep for their natural lifetimes: see "Designing the Unexpected"), has kept me on edge for the last couple of months. For new subscribers to Yarns, the shepherding saga began last autumn, as I tried to find a way to reconcile the principles of rotational grazing with the nutritional needs of the flock. At some level, I knew even back then I wasn’t giving the sheep what they needed when I first attempted HM-style rotation.

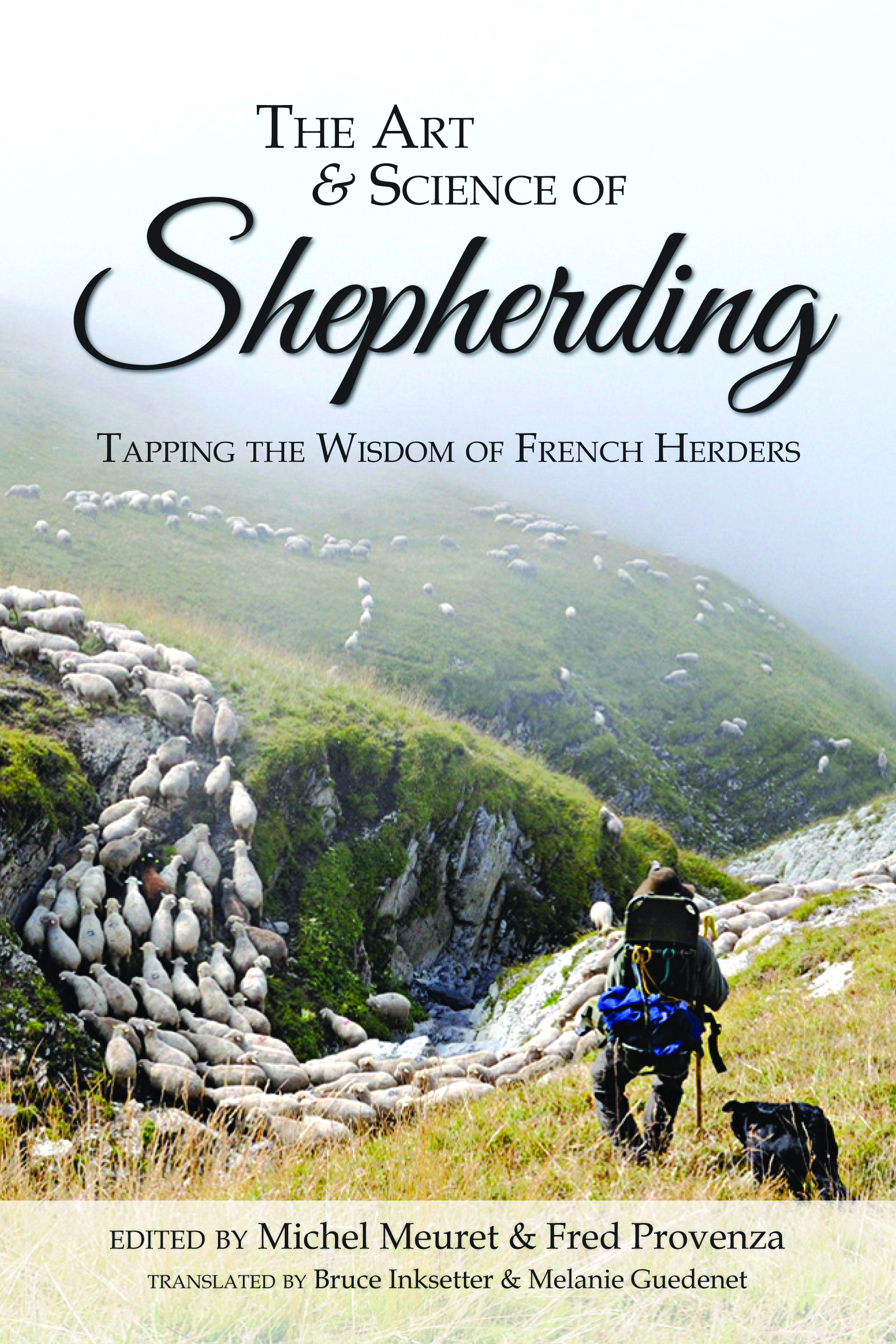

The first Yarn to talk about shepherding was “You Don’t Have to Be Perfect”, in March 2014. (And, by the way, all of the previous Yarns can be found on the website—click here for the full list. Also, I’ve posted a new video based on a talk I gave earlier this year, called “The Power of the Matriarch”.) The book “The Art and Science of Shepherding” by Michel Meuret and Fred Provenza has been my bible, and I am deeply grateful to Michel and Fred for their ongoing advice, and shoulders to cry on when things go awry.

Shepherding in the context of standard Australian paddock-style sheep management may seem a bit odd, and quite labour-intensive. Unlike European herders who manage flocks on unfenced common land, we are used to simply turning sheep out into paddocks, checking them periodically, and leaving them to their own devices when it comes to foraging.

So why put myself through the work of shepherding? Initially, I was trying mostly to improve pasture utilisation. Like humans, I think flocks get a bit lazy if there is plenty of food on offer. They don’t explore the corners of the paddocks, and they don’t utilise all of the different types of forage, especially the things we think of as weeds, like gorse and briar rose. Serendipitously, shepherding through this very dry spring has also allowed me to protect the main ironstone soil paddocks, and they are now carrying the sheep through the ongoing dry, with really quite good forage, considering the season. With a bit of luck and a little more rain, I won’t have to sell any of my sheep.

As I got more involved in shepherding, though, my motivation shifted to developing a better understanding of the flock—its needs and dynamics—and thereby improving my relationship with my sheep. The biggest single challenge for me in shepherding is aligning my human, rather driven, brain to the slow pace and “in-the-moment” experience of sheep. I would start the grazing circuit with a plan—generally a good one, as far as I could tell—and then spend most of the day frustrated because the sheep were not playing the game with me.

One day, watching from my kitchen window as the sheep grazed on their own, ever so slowly, through my big revegetation area, I realised I needed to find a whole new level of patience. They were moving at about a tenth the speed they do when I’m out there with them, trying to work my plan.

During the next grazing circuit, while the sheep were resting at mid-day, I had an epiphany. It wasn’t so much that I needed to be less impatient—rather, I needed to start from a different motivation, one that stays with the perspective of the flock, creating an experience for them that reflects all of what they really need: food and water, certainly, and also social interaction, rest, shelter, and time to simply be. As I thought this through, I realised I was describing the process of loving: holding the best interests of another being in your heart as well as your mind. It was an enlightening moment for me, and one I keep rediscovering, day by day. I guess that qualifies as both sweetness and light.

I hope all of you have a wonderful holiday season, filled with peace and the gift of love.

p.s. The swan family departed, on foot, in November. My theory is the rapidly shrinking Swan Lake was too small for flying lessons—they need lots of space to make landing mistakes. I may never know their fate, unless eight swans show up simultaneously in autumn for a visit.

p.p.s. Note added in press--wonderful thundershower this afternoon, pouring 8 mm (1/3 inch) on the farm in about 10 minutes, and finishing with a full-sky double rainbow. Hooray!