It is undoubtedly too early for me to write this Yarn. In fact, I’m not supposed to be writing at all today, on two counts: first, it’s meant to be a shepherding day, and secondly it’s a weekend and I’m supposed to turn my computer off for the weekend, to help break the "dumb gas thrall" syndrome. I’m not shepherding because it’s snowing and blowing a gale (this on the southern hemisphere equivalent of the first of May) and I just plain wimped out.

Mainly, though, it’s too early for me to write this because it’s going to take me years, maybe the rest of my working life, to really learn the Zen of shepherding. But in the spirit of sharing with you what I learn as it happens, here goes.

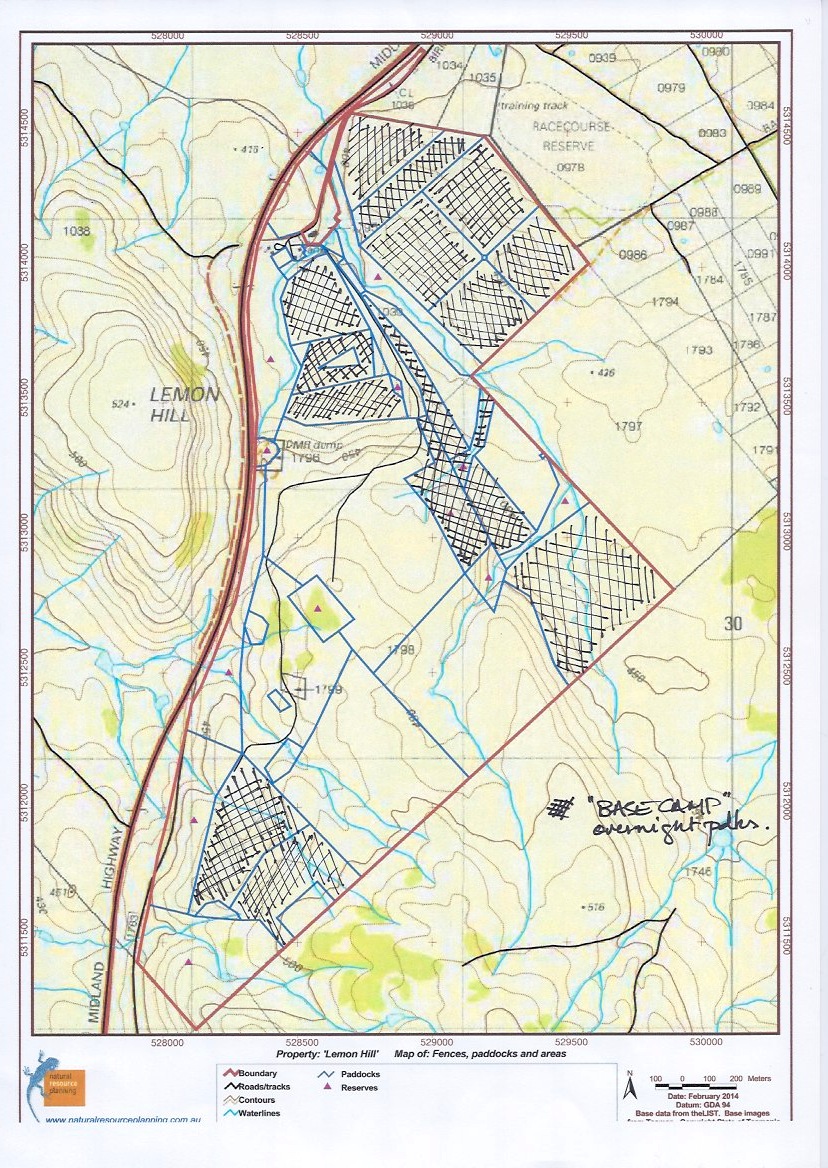

In France, for summer herding in the Alps, the sheep are brought in each night to a shed or night pen. They spend every day on the mountain with the shepherd and his or her dogs—they are not allowed to range freely at any time. Trying to mimic this approach, while working within my own constraints, I’ve started by dividing my property up into “overnight” paddocks and “mountain” paddocks.

Overnight paddocks are for the most part smaller and dominated by exotic grasses, particularly cocksfoot. Cocksfoot is grazing- and drought-tolerant, and hence can become quite rank. In contrast, my “mountain” paddocks have the lion’s share of biodiversity on the farm, and are less grazing-tolerant. In terms of carrying capacity, the property is about half “mountain” and half “overnight”.

My idea is to chaperone the flock whenever it is on the “mountain”—those are my shepherding days, and the flock is not allowed to overnight there. On alternate days, the flock is in one of the overnight paddocks—for 2 nights and the day in between. So, I’m shepherding 3 and ½ days a week, in theory: Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday (½ day), leaving me 3 and ½ days a week to run the yarn business and have a life.

I have no idea if this is the best way to go about shepherding on my place, but it seems like a reasonable place to start. On shepherding days, after I’ve done my morning chores (run the dogs, feed the dogs, feed the cats, feed me), I take my backpack, my crook and my two older working dogs, Chance and Janie, and head off on foot to collect up the flock.

The first part of the Zen is needing to work with the flock on foot, not from a vehicle—not even my little electric Polaris. Shepherding is all about relationships, starting with my physical presence. In my backpack are: my lunch, rain gear, spare socks, ground sheet, inflatable travel pillow, penny whistle, flask of tea, bottle of water, camera and binoculars.

You might notice that nowhere in that list is a book, my knitting, my iPad—all of which stay at home. I do take my phone for safety reasons, but I turn it off. Again, this is about relationships—with the flock, and also with the landscape, the wildlife, the weather, the dogs, and myself.

The second Zen thing is it’s not so much the physical challenge of walking all day and being in the weather as the emotional challenge of staying wholly present in the real world for hours at a stretch. Disallowing all my usual distractions means I am either focused on the flock or mentally idle. I find I am physically tired and mentally refreshed at the end of a shepherding day. And I find I am much more focused and calm on non-shepherding days.

On a good shepherding day, I manage to let Old Leader think she is making all the decisions, and as a result there is a wonderful flow: the flock is moving in its chosen forward biais and grazing with intent, until a collective decision is made to stop and rest. Rest times are variable, depending on the weather and also on the attractiveness of the forage. When we move into a new paddock, the energy level goes up sharply, and the sheep immediately move into an exploratory mode.

Sometime in the middle of the day, the flock generally settles down to ruminate and rest. And so does the shepherd and her dogs. In fact, if the weather is ok, I often have a short nap after I eat lunch (hence the travel pillow). There is a feeling of rightness about resting while the animals do. The dogs generally flake out—the only time they really switch off from work mode. And I find I always wake up a bit before the flock decides to move.

Re-establishing the biais after mid-day rest is one of my ongoing challenges. My lamentable tendency toward impatience often makes me prod them into action before they are ready, thereby annoying Old Leader and making the afternoon graze less serene. Also, I’m always a bit worried about getting them to the overnight paddock in good time, so I tend to hurry things along. Unfortunately, although we always seem to make the gate on time, if they haven’t been able to graze effectively on the way it rather defeats the purpose.

My own food on shepherding days is another Zen thing. Quite soon after I moved to full-day shepherding, my body started demanding a completely different regime: more diversity, more frequent meals—snacks, really, a strange order of choices and more calories. My “usual” lunch was simply not appealing. Boring, in fact. So I’m now trying to find different foods to pack in my lunch, never knowing for sure what my body is going to want at what point in the day. Is it the exercise? Hanging out with animals for whom feeding is a continuous process? Is it simply because my brain is more quiescent and my body can make itself heard? I don’t know. I just know I would never had predicted it.

And finally, the weather. As Zen as it gets. Shepherding is NOT like hiking, where you can change your pace if the weather comes in nasty, or even stop and pitch a tent and wait it out. The animals and I simply get to endure whatever the heavens send us. I never thought this would be a challenge for me, but I know now I’ve idealised the freedom of the outdoor life of shepherds and cowboys: there is a reason we humans build shelters, and it is not only to keep the rain off. It is also to help us feel less small and vulnerable in the face of the elements.

On rainy, blustery shepherding days, when I probably should be contemplating the journeys Siddartha made—with no rain gear at all—I find instead I am fantasising about inventing a one-woman-two-dog tent that weighs nothing at all, can be put up in a nanosecond, and would keep us warm and dry until the sheep are ready to move.