Blow, blow, thou winter wind,

Thou art not so unkind As man’s ingratitude…

Shakespeare As You Like It Act II, Scene VII

I have to take exception. With all due respect to the Bard, especially on the 400th anniversary of his death, the winter winds here have been exceedingly unkind. Perhaps I notice them more because I’m invariably facing them when the sheep are grazing slowly into the breeze. If I turn my back, I can’t keep track of the sheep.

Wind has been a part of my professional life since my graduate school days. Wind is the primary driver of ocean currents and waves, and also figures heavily in evaporation from the ocean surface, which in turn drives density-related flow. And the many months I spent at sea made me acutely conscious of wind speed and direction: when the ship is “on station” making a 4000m deep instrument cast for 4 or 5 hours, the ability of the officer on watch to hold position relative to the wire is critical. When you can’t anchor to hold the ship still, holding station is a delicate balance between windage on the ship and the gentlest of propulsion. When the wind is too strong, it becomes impossible, and the science crew just has to wait for conditions to improve.

However, nowhere in those sea-faring years did the speed, temperature and direction of the wind have as major an impact on me as it does now in shepherding. On the ship, it was always possible to hunker down behind a davit, or even sneak back into the lab to get out of the weather. Not so on the hill. And holding station means keeping the wind just on the starboard bow (the side from which, for whatever historical reason, it seems we always launched the tethered equipment). The wind couldn’t be full in our faces, or the windage would take the ship sideways and we’d end up with an unacceptably large “wire angle”.

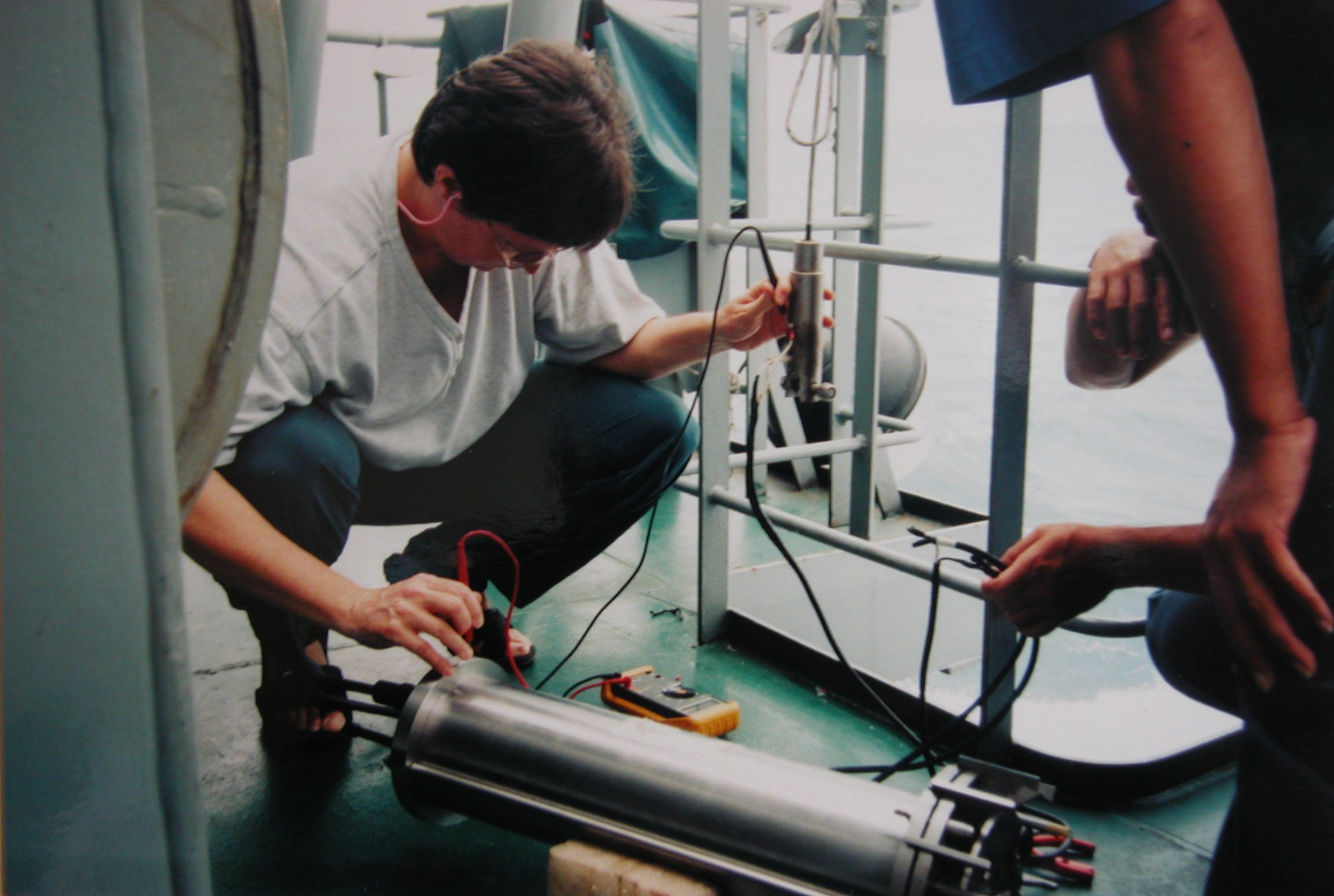

Heading out on a dive trip from the same vessel, to install a subsurface tide gauge in one of the many straits of the Indonesian Archipelago. I’m on the right, looking up, with my colleague Thomas Moore across from me. We had a number of rather exciting adventures towing large moorings into place with the Zodiac while battling strong tides and crosswinds.

Perhaps the most pernicious difference between going to sea and going shepherding is that sheep will invariably walk into the wind, if allowed. I’m quite sure this behaviour is linked to nutrition: they are smelling the plants available upwind, and working their way quite deliberately through the smorgasbord their noses sense. While I spend a certain amount of “travelling” time walking ahead of the sheep, as soon as I am ready for them to start grazing freely they overtake me and graze ahead, usually quite slowly, leaving me to the tender mercy of the winter wind in my face. Sometimes I can find the natural equivalent of a davit to hunker behind, but I can’t stay there long as I need to keep moving with the sheep. And in our mostly tree-less farming landscape, there aren’t a lot of davits to be found. All the more reason to persevere with tree-planting! And though it’s hard in the current circumstances to remember summer and being too warm, more shade trees would be a lovely addition.

With the onset of real winter, I am seeing a distinct change in eating patterns for the flock—they are seeking out gorse and other browse, and also are quite content to graze the new growth of cocksfoot, the rougher, tussocky grass at which they turn up their noses when there is fresh ryegrass available in spring and summer. The sheep are looking well, and getting used to having wet feet, or at least are less reluctant to cross small watercourses.

The choir I sing with—the Bagdad Community Singers—recently performed a musical version of Blow, Blow Thou Winter Wind, and when our wonderful choir leader Roslyn asked for real emotion in the following lines, I had not the least trouble summoning up a suitably fervent tone:

Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky, That dost not bite so nigh…

The swans have returned to Swan Lake and are busily nest-building. I took this video this morning. Very exciting!