Recovering from Shearing

It's just over two weeks since shearing, and we all seem to be more or less recovered. Shearing is the most stressful thing we do, in my humble opinion. Other than jetting for fly during the summer season, mostly the flock and the dogs and I just swan around the countryside doing what the sheep most want to do. So, having to squeeze 300 sheep at a time into the shed, allowing strange men to manhandle them (twice--once for crutching, then two days later for shearing), removing their 4" long wool coats and then putting them back on the hill to brave the cold, must come as a huge emotional, physical and thermal shock. The dogs have to work much harder than usual, too, because we really need the sheep to do precisely what's required, not approximately what they'd like to. And it's even hard on me, because I have to work to the shearers' schedule, which means a 5 am start, to get the dogs run and fed and the shed ready to go, before the shearers show up at 7 for a 7:30 (sharp!) start. I spend the day classing the wool, working 4 standard 2-hour runs along with the shearers, then after they've gone I do whatever stock work needs doing, run the dogs, feed the dogs (oh, yeah, on my 1-hr lunch break I have to start the slow-cookers for the next day's dog tucker), and when all that's done, about 7 pm, I come inside to an indignant cat who is more annoyed at my absence than truly hungry. As those of you who follow Come Shepherding will know, I just don't "do" days like this in the normal course of my shepherding life! This year and last, I've had a good paddock to put the sheep in after shearing: by removing the last of the original fences that separated the lucerne paddock from hill above it, I created about 100 acres of good feed connected to excellent shelter. They can find a spot out of the wind, no matter which way the wind is blowing. For the last two years, the shearers have also used "snow combs" that leave about ½ cm (¼ in) of wool on the sheep, to make them less susceptible to hypothermia. If it's raining, cold and the wind is blowing, freshly shorn sheep can easily die of exposure. Happily, both last year and this year the weather has been kind after shearing, and I think the sheep have adjusted fairly readily to their shorn condition. The other thing that happens, though, is that it's hard for me to recognise many of my sheep, because they truly look entirely different with their hair cut! It's mostly their behaviour in coming up to me and chewing on my pack straps that clues me into who I'm looking at.

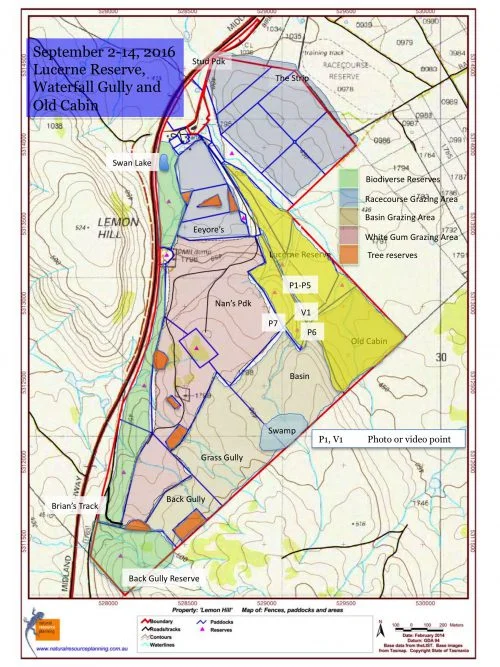

While we've been recovering, I haven't done any real shepherding, though I have opened up a couple of other adjacent areas for them to graze: Waterfall Gully and Old Cabin. I've also done quite a bit of experimenting with how the flock responds to me when I don't have any dogs with me. The "social contract", if you will, is principally between me + dogs and flock. The named sheep come to me, and the others follow them, but mostly because there is a dog force field behind them. I've been curious what would happen--what I'd be able to do as flock leader--without the dogs as backup.

The short answer is: there is a social contract between me and the flock in the absence of the dogs, but it's tenuous and fluid, and completely relies on the flock wanting to go in more or less the direction I'm trying to go. I assume that any emerging flock leader (ovine or human) would have a similar experience: the sheep will follow me when enough of them feel that my judgement is good. Otherwise, they simply ignore my overtures. Thus, if I am leading them into the wind when they are truly ready to move (rather than when half are still resting), toward a paddock with known good feed, and if I'm patient and quiet about it, I can get them to come with me for many hundreds of meters. However, if I'm trying to go downwind, or into any area with a memory of danger or fear, it's a snowball's chance in Hades that they will come with me.

Though this can be exceedingly frustrating in the moment, in the larger sense of leadership, it's a wonderful model. Imagine it at work in a modern democracy: active civil disobedience from the entire populace in the face of idiotic leadership. It would make for a much safer, happier, and more sensible world.

Taking time off shepherding has also given me the impetus to re-think the way I've been doing the Come Shepherding posts. It's been a fascinating process for me, and when I look back over the past 5 months I'm really glad I made the commitment. And, it's a LOT of work. I think I (and probably all of you, too) have gotten most of what is useful from a documentary description of shepherding on a day-by-day (and even hour-by-hour) basis. So I'm going to move to a format of something like once a week, with less daily detail but a more considered analysis of what I've learned over that week. I'll still post on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter, but not as many images. And I'll still provide a summary map (still working out how best to do it) for each post.

Here are a few videos and photos taken during the recovery from shearing period. Next post will be about managing the annual grasses and broadleaf plants in a year with a REAL spring!