During a recent podcast interview, I was asked to explain what I meant by a ‘conservation land ethic”, one of my three components of White Gum Wool production integrity. I have to say I struggled to answer the question succinctly, and even when I tried to be clear, found myself becoming quite emotional, nearing tears at a couple of points.

I know I have an intimate connection to the land for which I’m responsible. And I can articulate some of the more obvious ways in which my responsibility is conservationist and ethical, but I was shaken by just how emotional my response was, and how inarticulate I felt in trying to share it. This post is an attempt to explore the reasons why.

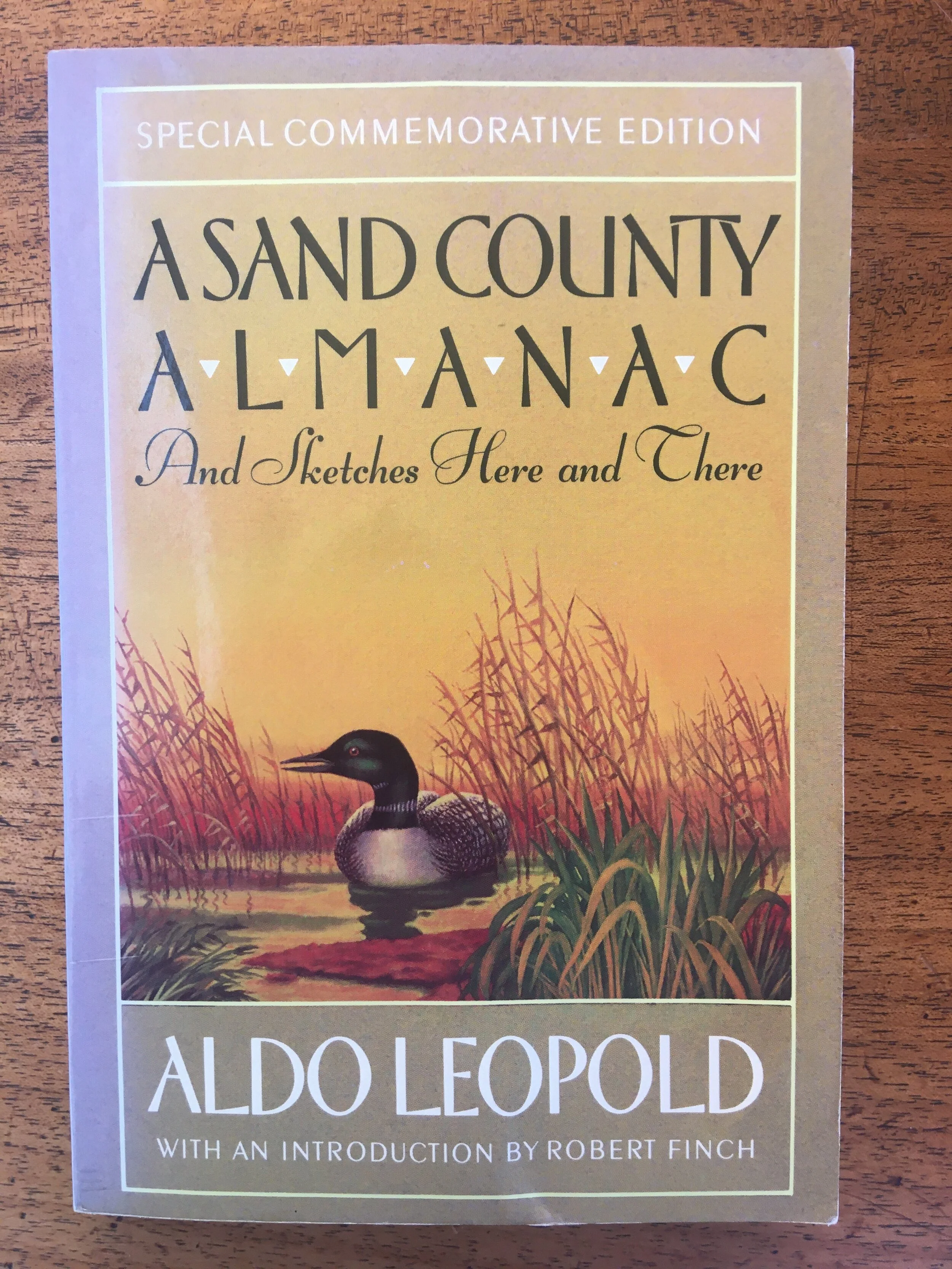

The term conservation land ethic comes from Aldo Leopold, a forester, conservationist, writer, and integrator, for lack of a better term. He lived in the first half of the 20th century, and was able to bring together his disparate life experiences and professional careers into a philosophy of land management—whether wilderness or agricultural—that puts the health of the land at the pointy end.

He defines an ecological ethic as “a limitation on freedom of action in the struggle for existence”, equating it with a philosophical ethic he describes as “a differentiation of social from anti-social conduct”.

In A Sand County Almanac, Leopold argued eloquently for the idea of human obligation to maintain the health of the land through what he called a conservation land ethic—the concept that land is to be loved and respected. While society has ethical rules to promote cooperation among humans, there are no land ethic rules dealing with our relationship to the land and the animals that live on it. “Land is still property. The land-relation is still strictly economic, entailing privileges but not obligations.”

While Aldo Leopold’s many essays on this topic are insightful and articulate, it is his short story, ‘Thinking Like a Mountain’ (also in A Sand County Almanac) that brought home to me the deep emotional connection to the land he developed over his lifetime. The story brought me to tears the first time I read it, 50 years ago, and to this day I find it impossible to describe without crying. And yet, it exemplifies the answer I was struggling to provide in the interview.